This is very strange. It’s a discussion on PBS — the Public Broadcasting Service — about Charles Darwin and economics. Reading the transcript (there’s also a video we haven’t watched) gives the impression of watching a pair of vegetarians discussing the best way to cook a steak. They may have some information, but they just can’t deal with it.

The PBS show is titled Was Charles Darwin the Father of Economics as Well? Below the video is a summary:

What does the work of Charles Darwin have to do with economics? As part of his reporting on Making Sen$e [sic] of financial news, Paul Solman talks to Robert H. Frank, author of “The Darwin Economy: Liberty, Competition, and the Common Good,” about the connection between economics and the father of evolution.

Your humble Curmudgeon has previously written a time or two about this subject. See Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand and Charles Darwin’s Natural Selection. There we said:

It has often been remarked that the theory of evolution, according to which life on earth evolves without the guidance of a designer, is remarkably similar to the way a free-enterprise economy develops, with each enterprise doing its best to prosper, yet without the “benefit” of a centralized planner.

We also wrote what is perhaps our favorite: Evolution, Intelligent Design, and Barack Obama, in which we said:

We suggest that Silicon Valley emerged in the complete absence of any stimulus package. Indeed, it probably emerged because there was no such package. Silicon Valley’s nurturing environment was a mix of entrepreneurial activity, venture capital financing, and an unregulated market. What we now know as Silicon Valley emerged without centralized planning — there was no “intelligent designer.”

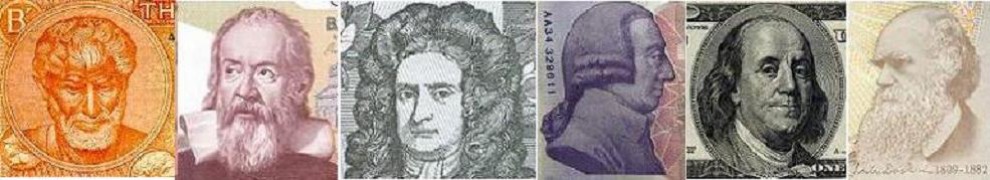

Okay, you know what we think — Darwin’s undirected mechanism of natural selection is strikingly analogous to the free enterprise economy described by Adam Smith, who said:

[E]very individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. … [H]e intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.

Now let’s see what PBS says about this subject. Here are some excerpts, with bold font added by us:

PAUL SOLMAN: There’s an idea war being waged over American economics. The left contends that greed and the market have become malign influences which must be brought to heel. The right, which blames government for most of what ails us, has a more positive view of greed.

Yeah, “greed.” Let’s read on:

ROBERT FRANK: The self-serving actions of greedy individuals will be channeled by market forces to produce the greatest good for all.

Greed, greed, greed. We continue:

PAUL SOLMAN: And so the right swears by the simple, invisible hand of free market competition, summed up here in simplistic graphics perhaps, but 18th century British thinker Adam Smith’s own timeless words. [Quoting Adam Smith:] “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”

That’s a correct statement. Here’s more:

ROBERT FRANK: A hundred years from now, if people poll professional economists, people like me, and ask, who’s the founder of your discipline, most people are going to say Charles Darwin.

Maybe, but it won’t be Frank who convinces anyone. You’ll see. Moving along:

PAUL SOLMAN: Thus, the invisible hand of natural selection promotes the survival of the individual and the prosperity of the species. In economic terms, this is the greatest good for the greatest number, the grand achievements of a market economy, made possible by competitive individuals like Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, or Steve Jobs.

These guys get some things right. And then they go off the tracks:

PAUL SOLMAN: Frank’s line of thinking continued to evolve. The winners were separating from the rest in almost every field, and their sky-high pay was fueling “Luxury Fever,” his 1999 book where he warned of competitive, conspicuous consumption among the super-rich, taunting and tempting us all.

An extremely insignificant and therefore stupid observation. Another excerpt:

ROBERT FRANK: There’s no question but that we’re in the midst of another Gilded Age. The robber barons had accumulated great wealth, and they spent it in very visible ways. The cyber-barons of today have accumulated great wealth, and they’re spending it in visible ways.

PAUL SOLMAN: Ways so visible that those down the ladder began emulating them. And that’s the downside of conspicuous competition, says Frank. With humans, as with other animals, the survival of the so-called fittest may come at a cost to the species as a whole.

That’s enough. These guys don’t get it. As the Discoveroids worship the “invisible hand” in biology, oblivious to the fact that Darwin explained it away, so too do the geniuses at PBS cling to the belief that free enterprise must be forcibly guided, being likewise oblivious to the fact that Adam Smith thought otherwise.

Copyright © 2011. The Sensuous Curmudgeon. All rights reserved.

I’m a big fan or Darwin, Smith, and Curmudgeon! And I agree with the analogy between economy and nature, mainly because I don’t think it’s an analogy at all. Nature is simply an economy full of individuals conducting transactions they hope are to their benefit. And overall life has been extremely successful, so it’s hard to argue with that! But as we know, in nature species can undergo population explosions, population collapses, and, of course, extinctions in response to changes in the environmental conditions. A species’ population collapse, for example, is just a free-market correction to a depletion of resources. Of course species don’t plan collectively on the basis of forecasts about future conditions. A completely unregulated human economy will operate in essentially the same way, and generally to the overall benefit of humans. But just as with nature, the economy can have bubbles and bursts, and so forth. In extreme cases, whole cultures can be (and have been) decimated. So my question for you is since humans have the rather unique ability in nature to collectively plan, under what circumstances would humans be justified in regulating or planning the economy in order to avoid at least the worst consequences of what are surely inevitable natural fluctuations?

Leviathan asks:

If a group of regulators could be found who had more knowledge and wisdom than the rest of the economy combined, perhaps an argument could be made that they should be running things.

I’m with Leviathan and also feel you moved the goalposts a little, Curmudgeon. I have no idea how one could regulate the economy -especially the global aspects – but do feel it should at least be considered. Leviathan’s point was that evolution has no ‘knowledge and wisdom’ or forecasting ability and neither does the economy.

Could we describe capitalism the way Churchill described democracy? As “the worst method of all….except for all the others.” I think capitalism can looked at as best system but that’s just another way of saying it is the least-bad.

surprisesaplenty says:

The economy does have foresight. Every business is aware that it requires raw materials, supplies, etc. They make contracts to acquire such things. They keep track of prices and trends. If there’s a scarcity, they make adjustments. Businesses do this stuff every day. The cumulative effect is reflected in market prices.

A bureaucrat, on the other hand, can’t possibly know more than the information already possessed by world markets. The only “advantage” a bureaucrat has is that he supposedly isn’t “tainted” by trying to make a profit. That doesn’t make him smarter or better than anyone else.

I think you misread a bit of the PBS segment. I watched it last night on the news hour. The examples of non-beneficial growth were more nuanced, and cultural, and not necessarily leading to a recommendation of some specific sort of regulatory regime. An example was of stags whose antlers have evolved to be very large, to enable them to win battles with other stags and thus have mating success. Those large racks carry with them the negative aspect of preventing the stag from running through dense woods and evade pursuing wolves. The point was some excesses by individuals and companies bring such social or economic success, that they are widely emulated by others (similar to inheritance) but those very excesses can bring economic disadvantage as well. If the excess is widespread, the result can be negative to the economy as a whole.

I think he has a point.

Also, there is a confusion here between regulation and central planning or control of the economy. Regulation, properly applied, can enhance the effectiveness of a free market economy. Anti-trust regulations are an obvious example, as are the regulations requiring disclosure of key information about products so consumers can make informed decisions. (economics 101 – a free market depends on informed consumers) Regulations can indeed be onerous – I worked a great deal with federal and defense acquisition regulations so I know this first hand. The fix, however, is not an unregulated economy. The fix is a smartly and efficiently regulated economy. No central planning, just clear rules of engagement that preserve the effective functioning of the free market, and prevent to the extent possible situations like the sub-prime mortgage debacle, which brought the entire economy to its knees. That entire situation could have been avoided, had appropriate constraints been in place on the ability to extend credit to consumers who could not repay it, and then securitize those loans into large funds and sell those funds to financial institutions, who then resold the funds, etc., all the while receiving AAA ratings from the agencies. That’s a simplistic summary, but it was a lack of key regulations which led to the recession, not the reverse.

Government can also make infrastructure investments (roads, for example) which boost the economy in many unforeseen ways.

Likewise the legal system, by preventing and punishing theft and fraud and enforcing contracts, is another kind of “infrastructure” which benefits the free market economy and doesn’t involve any kind of central planning.

Government economic regulations (anti-trust for instance) are a grey area where the legal system intrudes into the market without however necessarily leading down the slippery slope towards central planning.

Providing infrastructure which isn’t going to come about spontaneously by itself via the free market is something government should do; it benefits the free market and doesn’t need to involve any attempts at central planning.

To try to split the difference here–our arguments on these subjects always get us back into the same polarized camps with no one listening to each other–think of an analogy. Nobody tells individual molecules what to do, but by setting up a system with a few general principles you can harness their random motions into useful work. Overcomplicated machinery, however, juts gives you more stuff to break down and more routes to disperse potentially useful energy.

I doubt SC wants a completely unregulated market. No doubt he thinks markets should not sell human beings, there should not be murder contracts, it should not be legal to promise goods or services, take the money, and not deliver. The point that he (or I) would make is do we have more regulations than we need for optimal benefit?

I find it very, very difficult to believe we do not have enough and we need more. The USDA has federal inspectors to make sure that rabbits in magician’s acts are not mistreated, for example, and there are all sorts of Federal regulations on the handling and marketing of rabbits, of which most of us are unaware. But a few of us find out through hundred-thousand-dollar fines.

http://bobmccarty.com/category/politics-and-government/department-of-agriculture-usda/chasing-rabbits-department-of-agriculture-usda/

You would find it very hard to persuade me that this is a valid national concern, that we need the national government putting time and attention into this. If it is so damned important, surely it can be handled at the state or local level just like laws against murder and zoning regulations are handled. Any number of similar anecdotes regarding trivial matters that apparently require the expensive attention of Federal regulators can be cited besides these. We all know of ludicrous examples.

For example, the EPA has decided it wants the City of Corpus Christi to relocate entire neighborhoods at the expense of local industries, without bothering to consult anyone who actually lives there, though they did seek out the input of environmental activists who live elsewhere. Even though–and it bears repeating–EPA concedes that these industries are currently obeying all the environmental regulations that apply to them.

http://www.powerlineblog.com/archives/2011/11/environmental-injustice-at-the-epa-part-ii.php

They intend to simply order the industries to do this, under pain of losing their permits. Neither you nor I nor anyone else got to vote on whether these regulations should be used to force people to do things the law does not require. And yet they get used this way anyway.

That is a sign that there are too many regulations: that it is impossible to operate within them and have the government leave you to do what it is you do.

@mehProviding infrastructure which isn’t going to come about spontaneously by itself via the free market is something government should do; it benefits the free market and doesn’t need to involve any attempts at central planning.

Ah, a supporter of the Bridge to Nowhere.

http://biggovernment.com/tsteward/2011/11/09/empty-remodeled-minnesota-airport-lands-federal-grant-no-flights-or-passengers/

The St. Cloud Regional Airport is banking on a recently announced $750,000 federal grant to land an airline at the airport that’s been virtually deserted since Delta terminated service in and out of St. Cloud in late 2009. Despite a $5 million makeover of the terminal two years ago, St. Cloud’s airport has mostly sat idle as the city desperately seeks new commercial airline partners. St. Cloud received $750,000 in federal stimulus funding to assist with a portion of the renovation, but the project has thus far amounted to a passenger boarding bridge to nowhere.

Bulding infrastructure that people don’t need is simply a giveaway to corporations. I thought we were against that.

If that airport was worth flying out of, somebody would be making a profit offering flights. (St Cloud is about an hour and a half drive from MSP, which is a huge international airport.) What you really mean by government built infrastructure is that the government builds things that don’t make a profit and basically gives them away to people who didn’t pay for them. That’s how we get utilities–and they are given a monopoly in exchange. It’s crony capitalism and i’m surprised to see you espouse it. But I guess we’ve been watching Rachel Maddow on the Hoover Dam.

Which would never be built today in our current regulatory climate. The Pat Tillman bridge that goes over Hoover Dam was built at a cost of $240 million and took 22 years, from the environmental study in 1988 to opening day in 2010.

The ACTUAL DAM was built in FIVE years. At a cost of $49 million, which is about $800 million in today’s money.

Ed says:

Surely you realize that bankers know how to assess the credit-worthiness of their customers. That’s what they do. They don’t need regulators for that. It was regulators who told them they had to ignore the principles of sound banking by making those sub-prime mortgage loans.

The infrastructure argument goes right back to Bastiat. You see that the government took tax money away from people and built a road, or a bridge, or a dam. And you point to that thing and say look what the government built.

But what you do NOT see, is the things that COULD have been built if people had been allowed to spend their money as they saw fit. They did not see fit to build that road or bridge or dam because they chose not to. They expressed a preference for not having it in how they chose to spend their money. If they’d wanted that thing they’d have got a company together, invested their money, and built it. Just like with the cell phone networks (though they were set back over a decade while waiting for FCC approval).

Of course, it may not have been POSSIBLE for them to do it–building infrastructure is now beset by so many regulations that it is illegal to do these things without the government’s permission, without many years of studies, lawsuits from activists who oppose the building of anything, and the like.

So the governmnent’s building of infrastructure is the answer to a problem the government caused. God forbid people be allowed to build the things they need without getting someone’s permission.

@SC:

It was regulators who told them they had to ignore the principles of sound banking by making those sub-prime mortgage loans.

And when the government forced banks to make risky loans, banks diabolically sought to reduce this risk that they did not choose to accept, by getting into credit default swaps. How dare they!

But credit as a civil right is not enough. What good is credit without money? And not every kind of purchase can be made with a credit card. Hence I propose the Slacker Brother-In-Law Act of 2012. Everyone above a certain income level will be required to lend their shiftless brothers-in-law up to $5000, interest-free, every calendar year. It can’t fail to stimulate the growth of our weed, porn, and video game industries at this critical time, and thus directly lead to job creation. As for getting paid back, that’s YOUR problem.

Gabriel Hanna says: “I propose the Slacker Brother-In-Law Act of 2012”

Good idea! It’s not enough to spread the wealth around. We must also spread the credit around. That will lead to a truly just society.

“It was regulators who told them they had to ignore the principles of sound banking by making those sub-prime mortgage loans.”

Please explain to me Northern Rock driving itself into bankruptcy with sub prime mortgages without these regulations. Explain Barclays bank having to right off billions without these regulations. Explain how Santander Bank went from a major European bank to one of Europe’s elite banks by being limited in how much it could dabble in sub prime mortgages by regulations. So their losses were minimal when the crash happened?

“Surely you realize that bankers know how to assess the credit-worthiness of their customers”

The bankers did, their bosses did not care. My brother worked for a major banking concern during the bubble of sub prime mortgages, as a mortgage advisor. He was constantly being told he was turning down too many mortgages, and that he was looking too closely at the income claims of applicants. His bosses only cared about the bonuses they would earn, based on successful mortgage applications, and not about the future of these mortgages.

Let me clarify this bit:They expressed a preference for not having it in how they chose to spend their money. If they’d wanted that thing they’d have got a company together, invested their money, and built it.

I realized I have to modify it. These people who did not “want” the dam, road, bridge etc. did not want it badly enough to SPEND THEIR OWN MONEY. They might have been, and indeed usually are, perfectly happy to have these things provided that SOMEBODY ELSE pays for them. Enter the government.

And this is why all of us living outside of Montana have been paying to have roads built there, which most of us will never use, even indirectly. This is why Hawaii has an interstate. This is why Nebraska gets counter-terrorism money. This is why when I rode the bus daily to campus at WSU people in Yakima and Puyallup and Seattle were paying for my ride.

Flakey says:

I know nothing about them. There have always been banks that manage to go bust. That’s not an argument for the extraordinary level of regulations we have today.

@Flakey:

He was constantly being told he was turning down too many mortgages, and that he was looking too closely at the income claims of applicants. His bosses only cared about the bonuses they would earn, based on successful mortgage applications, and not about the future of these mortgages.

And of course, they had no concern whatever about violating the law by turning down credit applications. It was all greed for bonuses.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Community_Reinvestment_Act

I don’t believe that anyone here has claimed every institution that lost money in the last five years lost it solely because of the law, so I’m not sure what you think citing foreign banks proves, except that financial markets in one conutry are affected by those in another.

SC says:

This is true. However, almost all subprime (and “alt-A”) mortgages were sold off in derivative instruments to other financial institutions. The originators, who were primarily brokers of various types (many were private label firms owned by commercial banks) and not traditional banks, never intended to hold the loan. They made their money through the fees charged in connection with the loans, and the more loans they could write, the more money they could make. When they securitized the loans and sold them, they then obtained the capital required to extend new loans, and the cycle repeated. The separation between the originating organization and the eventual risk-holding organization, in my view, is the single most important contributing factor to the mortgage crisis. Organizations like traditional banks and credit unions, who held the risk for the mortgages they originated, definitely assessed the credit-worthiness of their customers. They weren’t writing subprime mortgages (WAMU being a notable exception). Even those banks who tried to cash in, like Wells Fargo, did it through subsidiary organizations.

@Ed:The separation between the originating organization and the eventual risk-holding organization, in my view, is the single most important contributing factor to the mortgage crisis.

Assuming that your view of the situation is correct, what sort of regulation do you propose–and how do you know that the unintended consequences of that regulation will not end up making the economy worse off than it would be without it?

As an example: the South Sea Bubble was caused by speculators who had no intention of investing in a company, selling stock to each other at more and more inflated prices (much like the dot.com boom 200 years later). Should trading in stocks have been banned? (Should trading in tulips have been banned after the tulip mania?)

It was ever thus. That’s what “market” MEANS. Very few of us buy anything directly from “originators”. Instead, we buy them from “middlemen” and “speculators” who are hoping to profit.

Let’s not forget the role of F & F in creating the mess.

F & F lowered lending standards and encouraged loaning to what were previously deemed less than creditworthy borrowers by offering to buy those high risk loans. Few, if any, risky loans were made without F & F giving an okay. Loan originators basically said to themselves — hey, if F & F says it’s okay and will take this loan off my hands, why not make the loan and make a few bucks?

F & F then took those risky loans and bundled them up with good ones, creating mortgage backed securities upon which they gave the AAA quality debt government approved stamp. Many investors all around the world, including foreign governments and banks, bought those securities thinking they were solid conservative investments, almost as good as US Treasuries.

F & F was doing the bidding of the politicians engaging in social and financial engineering — “everyone should be able to buy and own a home”.

This “well intentioned” meddling in the market undermined and destroyed what had previously been an extremely stable real estate and mortgage debt market for over half a century.

“And of course, they had no concern whatever about violating the law by turning down credit applications. It was all greed for bonuses.”

Of course not, That was an American law, and had no bearing on my brother. What pervaded the UK banking industry at the time was only partially greed, but more a huge focus on the quarter results, some on yearly results, and practically no long term thinking.

“I know nothing about them. There have always been banks that manage to go bust. That’s not an argument for the extraordinary level of regulations we have today.”

IT was not an argument for that. I was directly quoting your insistence that it was the regulations that caused the sub prime bubble. When European banks managed to get in just as much difficulty as American banks, without the regulation that “forced” America banks to lend. It is my contention even without that regulation, American banks would have generated just as much trouble for themselves, as with the regulation. Just like most European ones did..

Your quote again

“It was regulators who told them they had to ignore the principles of sound banking by making those sub-prime mortgage loans.”

In America you claim it was regulation that forced banks to ignore sound banking, how do you explain European banks doing exactly the same thing, without a regulation forcing them to loan?

Most Excellent Curmudgeon, I do greatly admire the professed purity of your conviction! But as when encountering neutrinos from Oklahoma, I feel compelled by my scientific sensibilities to conduct further tests to confirm the exact nature of your disposition. So I humbly seek your reaction to the following example. The FAA requires aircraft OEMs to demonstrate through extensive design documentation and flight testing that their products are airworthy. Further, they require of airlines certain levels of maintenance and inspection, not to mention training for their pilots and mechanics. Enforcement of these regulations takes considerable money from the pockets of us taxpayers, not to mention the costs, passed on to travelers, of companies complying with these copious regulations. Further, these regulations concentrate some of the decision-making about the market for air travel in the hands of a few people with expertise in the design, manufacture, and operation of aircraft. Do you therefore advocate for the doing away of the FAA, thereby letting the air travel market, and hence the quality of flight equipment and the competency of flight operators, be guided, unfettered, by the choices of travelers, all making individual decisions according to their own knowledge of airplanes and airplane operation, their ability to pay, and their willingness to accept risk?

Leviathan asks: “Do you therefore advocate for the doing away of the FAA”

It amazes me that when anyone says: “These regulations are unnecessary and burdensome,” the almost guaranteed response is: “Aha, then you favor anarchy, no laws whatsoever, unbridled fraud, uncontrolled marketing of diseased food, etc.” Surely you can sense a false dichotomy in there.

Anyway, much of what the FAA does is fine and necessary. I don’t know why they control who gets what routes, but I’m no expert on that stuff. I also think that safe aircraft design and maintenance can be assured to the consumer by means other than government agencies — Underwriters Laboratories is an excellent example of a private quality control technique. As for flight plans and such, that’s necessary, but there’s no reason why it has to be done by a government agency. Railroads somehow manage to schedule the use of all the tracks in the nation without bureaucratic assistance.

Bottom line: I think most of what the FAA does that needs to be done could be effectively privatized, probably at lower cost. That’s true of a great many other bureaucracies.

Thank you for the response. And rest assured that I do not suspect you of being an anarchist! And I swear that false dichotomies are my least favorite kind of dichotomy–for instance, “legitimate functions of government are the ones I like, and the rest are regulations…” I don’t like straw men either, so I hope that wasn’t one! 🙂

Regarding “We suggest that Silicon Valley emerged in the complete absence of any stimulus package. Indeed, it probably emerged because there was no such package. Silicon Valley’s nurturing environment was a mix of entrepreneurial activity, venture capital financing, and an unregulated market. What we now know as Silicon Valley emerged without centralized planning — there was no “intelligent designer.” Have you considered what Silicon Valley would be without the Internet? Can you imagine private companies creating the Internet? Anyone advocating “all private” or “all public” economies are deluded. The trick is to find the balance between public and private contributions to the greater good.

Regarding: “I think most of what the FAA does that needs to be done could be effectively privatized, probably at lower cost. That’s true of a great many other bureaucracies.” I think you are missing the point of government bureaucracies. Think about what happens when things go horribly wrong (Hurricane Katrina, etc.). If a private “regulating” or “overseeing” company is to blame for some egregious fault, what are we going to do? Bankrupt the agency that regulates our airlines or monitors the safety of our food, etc? How would you replace such companies? Since they would have a monopoly on their function, someone else would have to start from scratch to replace them. There are things we want the government (meaning us, our representatives) to be responsible for, so we can punish malefactors (or their supervisors) at the ballot box. Like a baseball team, sometimes you fire the manager because you can;t fire the whole team.

@Gabe:

Regulations requiring disclosure of important information to investors would have helped. For example, if brokers who were bundling the mortgages and reselling them were required to clearly disclose the percentages of traditional, jumbo, alt-A and subprime loans that were in their instruments, there would have been greater scrutiny by buyers, and a more realistic valuation of risk. The rating agencies would most likely have given a lower overall score to the instruments had they known the percentages of subprime loans contained within them. If risk is accurately built into the price of an instrument, the financial system can absorb the impact when it goes bad. My dream regulation would be some sort of classification system where a type “A” mortgage-backed security would contain only traditional mortgages, a type “B” would contain up to 10% alternative mortgages, a type “C” which would contain up to 20% higher risk loans, etc. The higher risk types would be discounted by the market, but if house values continued to rise and defaults were at a minimum, the return on those funds would be much higher. When the housing bubble burst, financial institutions would have been able to accurately write down their investments and the flow of money would not have been interrupted.

I would like to see limits on the amounts that brokers or bankers can charge for “loan origination fees”. That would have limited the business in subprime loans by removing much of the reward for writing them, however I understand that fees in general are subject to market forces and would normally be limited by the competitive market itself.

Even the FAA has started to get a clue, spinning off the design standards responsibility for Light Sport (LSA) Category to the industry itself, which has worked through the private standards org ASTM to formalize them.

http://www.astm.org/SNEWS/ND_2008/stephensons_nd08.html

In its modern laissez-faire meaning, the “invisible hand” metaphor predicts, in many cases, outcomes for consumers that are far from ideal.

Consider drug manufacturing. The most profitable drugs are the ones patients take in frequent maintenance doses to control some chronic condition: high blood pressure, allergies, impotence, and so on. Almost as good are palliatives for conditions that frequently recur, whether treated or not: colds, flu, headaches, and so on.

Drug companies have an incentive, then, to focus research and development (and advertising dollars that might otherwise go into R&D) on drugs a patient is likely to use for a lifetime at the expense of drugs designed to provide a permanent cure for these or other conditions.

I’m not propounding a conspiracy theory here; it could be that all drug company executives act entirely in selfless probity when they decide how to allocate resources. Indeed, the eradication of smallpox and near-eradication of polio demonstrate that optimal results are possible. Note, though, that there was significant government involvement in these outcomes.

I am a little late to the party and Flakey has already touched on this in a roundabout manner, but this statement is not true. In fact, precious few of the subprime loans were written by banks not subject to the Community Reinvestment Act. See Here.

In short, the government did not force banks to make loans to unworthy customers. Furthermore, the government did not force the large investment banks to package those shitty loans up into big piles of crap called Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs). Nor did the government force the investments to submit those CDOs to the ratings agencies. And the government didn’t force the ratings agencies to give those big piles of crap investment grade ratings that were totalling divorced from the worthiness of the underlying loans. And the government didn’t force the investment banks to take those CDOs and risk-divorced ratings to AIG (and the like) to get Credit Default Swaps (CDS) against those CDOs. Nor did the government force those companies to write the CDS’ at premiums far below what should have been charged given the actual inherent risks. Nor did goverment force the underwriters to package and sell the income stream from the CDS as synthetic CDOs.

All this was done by a handful of large banks that are “too big to fail,” thus introducing yet another layer of moral hazard that means while profits accrue into private hands (which they should), losses are socialized. And, to top it all off, the post-meltdown regulation that did get put into place does precious little to solve any of this. Further, I would suggest that the end result of this whole bubble was only to enrich bankers and inflate the housing stock to unsustainable levels, thus depressing home prices (a vast majority of most peoples wealth) for decades. That money all would have better utilized invested in nascent, innovating industries. So, not only did the bubble take a huge chunk out of most people’s current wealth, it also likely served to inhibit economic growth for many years to come.

I haven’t been able to find any study of such, but you cannot ignore that there is a fair amount of government regulation that wasn’t written by a bureaucrat in order to constrain industry, but was actually written by industry to constrain competition. It is called rent seeking.

The CRA was but one arm of the government octopus that manipulated the housing market, and to focus on it exclusively is to miss the bigger picture — which is that government policies caused a massive deterioration in mortgage underwriting standards for both sub-prime and non-subprime loans alike, causing an explosion in “non-traditional mortgages” with little down payment, which vastly increased leverage and profit potential, which fueled the expansion in housing demand that was the housing bubble. Evidence for this includes the explosion in loans that had 3% or less down payment, which goes from a near zero % of all mortgages up to the early ’90s to 40% of all mortgages by 2007.

Click to access Pinto-Government-Housing-Policies-in-the-Lead-up-to-the-Financial-Crisis-Word-2003-2.5.11.pdf

Lots of good comments above. A few observations follow on the concept of “optimal” which both Gabriel Hannah and Retired Prof have used explicitly to argue their positions, but their differing assumptions of optimality also appear either implicitly in other’s comments, or explicitly in The Curmudgeon’s earlier posts on the topic of Darwin in economics.

Gabriel Hannah says: “…[M]arkets should not sell human beings, there should not be murder contracts, it should not be legal to promise goods or services, take the money, and not deliver. The point that he [The Curmudgeon](or I ) would make is do we have more regulations than we need for optimal benefit?”

Retired Prof says: “Indeed, the eradication of smallpox and near-eradication of polio demonstrate that optimal results are possible. Note, though, that there was significant government involvement in these outcomes.”

So not having read Robert Frank’s book regarding Darwin and economic theory, I’m curious to find out exactly how he does connect Darwin to economic theory. But the thing is, economic theories are usually framed by their advocates that one above all is the true optimizing solution. But, evolution is decidedly and fundamentally not an optimizing process. Instead, evolution has been described as a “satisficing” process – a combination of “satisfactory and “sufficient”.

So in biology, Dawkins gives the example of the insane routing of the recurrent laryngeal nerve as being a satisfactory and sufficient way to adapt an ancient thorax architecture to accommodate the plumbing of the four chamber heart we mammals use. The routing of the nerve is not a biological sign of ID.

In technology, we always get less than optimal performance because it is satisfactory and sufficient to employ software patches to the hardware and architecture of existing infrastructure that we already rely on. So once Microsoft became the default platform for consumer PCs, even Microsoft can’t optimize it. The ubiquitous presence of Microsoft based PCs is certainly not a technological sign of ID.

And therefore in economics we must be willing to accept less than the optimal performance which one or another philosophy of economics will always promise is the optimal one. In the real world there simply is no way to implement any optimal idea, unless you are willing to adopt Ray Comfort’s argument that the banana represents the optimal design for food.

And therein lies the current problem. We are watching the political scene, and noting a cross pollination of doctrinaire economics theory with evangelical theocratic politics. Sternly Objectivist economic views easily find fertile ground among a growing part of the electorate which has no particular problems, and even embraces, an end of times societal collapse. Optimal for them maybe, but not for me.

So while there is rationality in arguing for free market economics among those who all understand the concept of a free market of ideas and the consequences of those ideas, I would suggest that it would be irrational to incorporate as political allies those who hold pre suppositional concepts of designed optimality.

Rather than exploring Darwin in support of one’s economic philosophy, I would rather take the counsel of Machiavelli who said that while it is better for a ruler to be feared than loved, above all else the ruler must avoid being hated.